The Print in the Painting

Many Spanish Colonial paintings depicting prints have survived to our day—see, for example, the adjoining painting of Saint Peter by Nicolás Rodríguez Juárez (1667-1734). These paintings reveal a good deal about the use and importance of prints in the Spanish colonies. Some of these paintings have been gathered here.

Many Spanish Colonial paintings depicting prints have survived to our day—see, for example, the adjoining painting of Saint Peter by Nicolás Rodríguez Juárez (1667-1734). These paintings reveal a good deal about the use and importance of prints in the Spanish colonies. Some of these paintings have been gathered here.

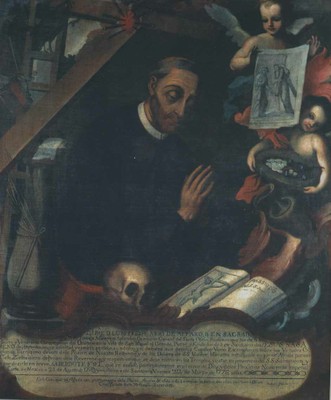

Judging from these paintings, we can see that prints were attached to the walls of domestic or monastic interiors, serving as aids to private piety--and therefore also as witnesses thereof (Figs. 1-11). Prints were also used in isolated churches or faraway missions that did not have paintings yet (cf. Neuerburg 1985). In this they contrasted with murals and large format paintings displayed at public places of established indoctrination, worship, or contemplation, like schools, churches, or monasteries. Prints were also available loose or bound in books. And could even be borne by angelic or divine creatures (Figs. 5, 6).

Of special interest in this regard are two series of unusual paintings of martyred apostles. One of them is found in the Capilla del Espíritu Santo in San Luis Potosí, México; the other in the Paraninfo Universitario of the Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca. The former shows angels descending as each of the apostles is being martyred. The angel bears a palm of martyrdom, a crown of laurel, and a print bearing the name of the apostle—as if to reassure the martyr that posterity will acknowledge his martyrdom (see here). The other series also contains angels presenting prints—but this time to the viewer, so as to present the martyrs to us as paragons of faith (see here).

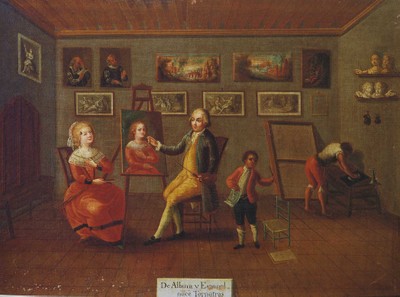

But prints did not have only devotional value. Profane woodcuts or engravings could be used as forms of simple ornament (Figs. 12-13). Most importantly for our project, however, prints were used in artists' workshops, where they were both created and displayed (Fig. 14)—and even used actively as models (Fig. 15).

Most of the time, prints were simply tacked or nailed against walls, where they could scroll or tear (Fig. 9). If frames were used at all, they tended to be simple ones. They were thin and made of wood left unvarnished and unpainted. Occasionally, however, prints were inserted into somewhat more elaborate frames (Fig. 11). They could also be illuminated--sometimes so thoroughly that they passed for actual paintings (see Historia del Arte Colombiano, III, 801ff).

|

|

|

| Fig. 1. Mexican School, Fray Francisco de Santa Ana. |

Fig. 2. Cristóbal Lozano, Padre Martín de Andrés Pérez |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 3. José Mariano del Castillo (attr), Sor María Clara Josefa |

Fig. 4. Anonymous, Dr. Francisco Gutiérrez | |

|

|

|

| Fig. 5. Anonymous, Luis Felipe Neri de Alfaro | Fig. 6. José de Ibarra, El Niño Jesús y los Cánones de Puebla |

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 7. Mateo Paz, San Pedro Nolasco (detail) | Fig. 8. Anonymous, San Juan Nepomuceno | |

|

|

|

| Fig. 9. Laureano Dávila, Santa Rosa de Lima meets with the Inquisition (detail). |

Fig. 10. Taller de los hermanos Cabrera, La Buena Muerte | |

|

|

|

| Fig. 11. Anonymous, Exvoto al Señor Aparecido (detail) | Fig. 12. Anonymous, De Español y Morisca Nace Albino | |

|

|

|

| Fig. 13. Anonymous, De Español y Morisca Nace Albino | Fig. 14. Anonymous, De Español y Albina Nace Tornatrás | |

|

||

| Fig. 15. Anonymous, Saint Luke painting the Virgin in his studio |

Sources of the Figures

0. Concepción García Sáiz, "Catálogo". Un Arte Nuevo para un Nuevo Mundo: La Colección de Arte Virreinal del Museo de América de Madrid en Bogotá. Exhibition Catalog - November 23, 2004 - February 27, 2005. Madrid, Museo de América, 2004, cat. 28.

1. Treasures of Mexico/Tesoros de México. Exhibition Catalog. Los Angeles, Southern California Graphics Corp, 1978 p. 40.

2. Museo de Arte del Centro Cultural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú (Foto: Enrique Quispe Cueva).

3. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Catálogo Comentado del Acervo del Museo de Arte. Nueva España, Tomo II. Mexico, 2004, p. 150.

4. Museo de Arte del Centro Cultural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú (Foto: Enrique Quispe Cueva)

5. José de Santiago Silva, Atotonilco. Alfaro y Pocasangre. México, Ediciones La Rana, 2004, p. 82.

6. Arts in Latin America 1492-1820. Exhibition Catalog. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2006, p. 332.

7. Banco de Crédito del Perú, Visión y Símbolos. Del Virreinato Criollo a la República Peruana. Lima, 2006. p. 126.

8. Museo del ex-Convento de Santa Mónica, Puebla. Photo credit: Aaron Hyman.

9. Luis Mebold SDB, Catálogo de Pintura Colonial en Chile. Santiago, Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile, 1987, p. 347.

10. Chile Mestizo. Tesoros Coloniales. Catálogo de Exposición. Santiago de Chile, Centro Cultural Palacio La Moneda, 2009, p. 159.

11. Museo Franz Meyer/Artes de México, Retablos y Exvotos. México, Impresiones Fotomecánicas SA, 2000, pp. 4-5.

12. Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting. Images of Race in 18th Century Mexico. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2004, fig. 129.

13. Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting. Images of Race in 18th Century Mexico. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2004, fig. 183.

14 Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting. Images of Race in 18th Century Mexico. New Haven, Yale University Press, 2004, fig. 184.

15. Tacho Juárez Herrera Photostream (this painting is located at the Parroquia San Lucas Xolox, Tecamac, Estado de México).

Almerindo E. Ojeda

Last Revised: April 11, 2020